There is always a point in the year when someone pulls up the latest democracy rankings and tries to guess who climbed, who slipped, and who managed to defy expectations.

The 2025 edition of the Democracy Index lands with a tone that is hard to miss. The Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) lays everything out in the annual report covering political conditions during 2024, and the message is bleak enough to stop even the most optimistic reader mid-sip.

The headline is direct. Even with the world experiencing an extraordinary year of national elections, democracy continued to erode. EIU reports a global average score of 5.17, down from 5.23. That number carries weight because EIU says it is the lowest global score since the index began in 2006.

The idea that billions of people went to the polls while freedom indicators fell creates a strange kind of tension. It invites a careful look at what the index actually measures, where the slippage happened, and which countries are bucking the trend.

Let us take it section by section, using the EIU framework and cross-checking those signals with other major democracy trackers that also released 2025-cycle updates.

Table of Contents

ToggleHow the Democracy Index Works

Before looking at winners, strugglers, or surprises, a quick grounding in EIU’s approach helps set expectations.

EIU measures 167 countries and territories, using 60 separate indicators spread across five categories.

Five Categories in the Index

- Electoral process and pluralism

- Functioning of the government

- Political participation

- Political culture

- Civil liberties

Each category runs on a zero-to-ten scale. The overall national score is the average of all five.

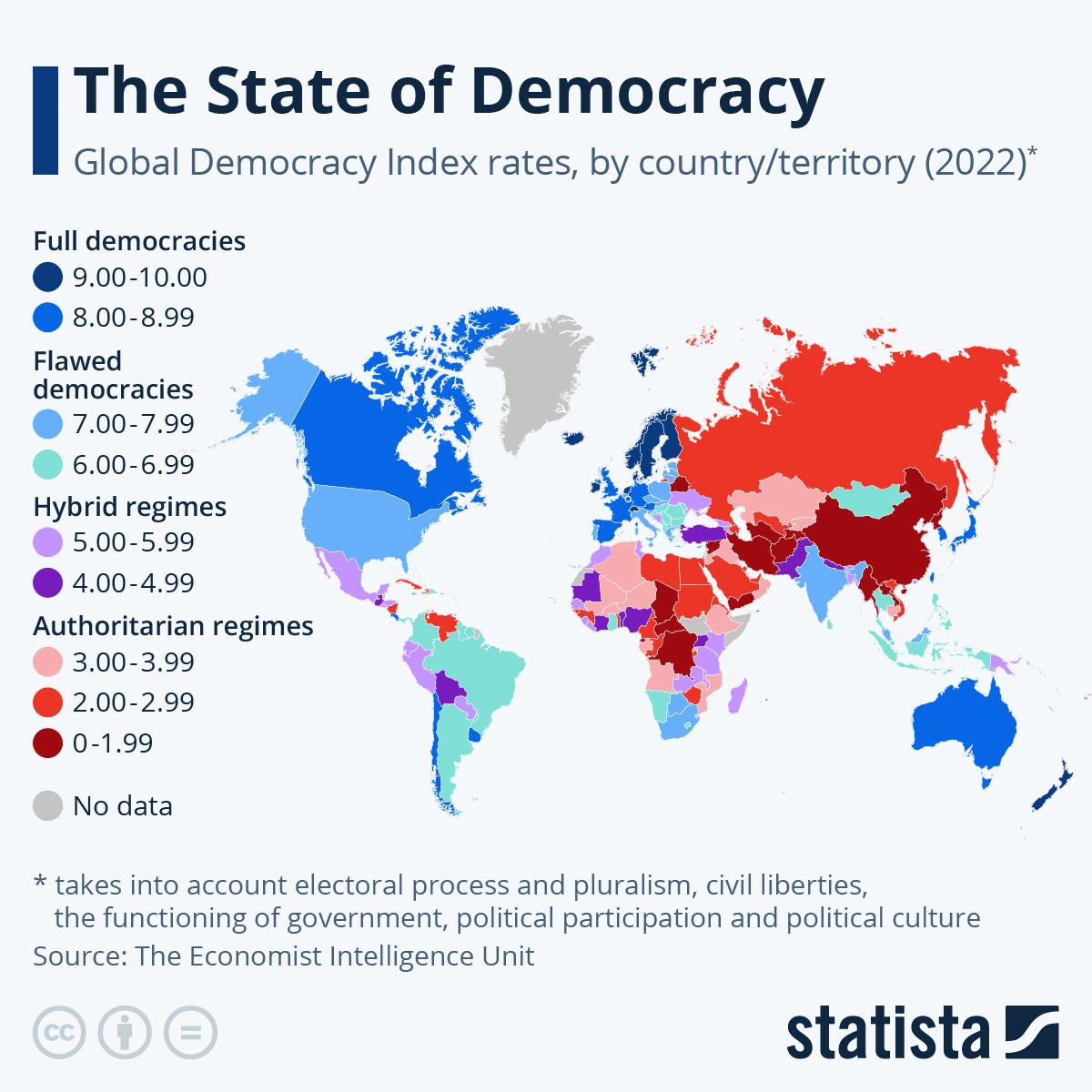

EIU then assigns each country to one of four regime types:

- Full democracies

- Flawed democracies

- Hybrid regimes

- Authoritarian regimes

That classification shapes the public conversation because it is simple enough to reach wide audiences but detailed enough to highlight real institutional differences.

What the Index Does Not Claim to Measure

EIU is not ranking countries by economic performance, geopolitical alignment, military power, or cultural cohesion. It is entirely focused on democratic quality.

It does not assume elections alone define democracy, and it does not automatically grant high scores to countries with competitive multi-party systems if civil liberties or rule-of-law conditions are slipping.

How to Read Drops and Gains

When a country’s score moves, the key is to look at the specific category where trouble appears. EIU itself points readers to a few recurring patterns.

Common causes of decline

- Electoral process and pluralism: unfair rules, intimidation, or administrative capture

- Functioning of government: corruption or unchecked executive power

- Political participation: shrinking space for opposition groups or civic activism

- Political culture: tolerance for authoritarian shortcuts or polarization

- Civil liberties: limits on speech, press, assembly, personal rights, and due process

EIU also writes that long-term deterioration is strongest in civil liberties and the electoral process. Those slow declines matter because they often signal deeper stress than a single chaotic election year.

Global Picture for 2024 Scores, Published in 2025

The global context is crucial. More than half of humanity voted in national elections during 2024, from India to the United States to Mexico to South Africa.

In the USA, the election was a Red vs Blue battle, and other countries faced their own versions of it. Even the most liberal cities in the US marked some decline on the blue side.

EIU argues that the wave of elections did not generate a wave of democratic renewal. Instead, the world slid further.

2025’s Headline Numbers

- Global average score: 5.17

- Global trend: continued erosion

- Year-on-year shift: negative, confirmed by EIU as the lowest average since 2006

How Many People Live Under Which Kind of Political System

EIU uses population shares to paint an even sharper picture:

- 45 percent live in a democracy

- 39 percent live under authoritarian rule

- 15 percent live in hybrid regimes

Those percentages come from EIU’s own summary of political conditions, not from raw country counts.

Country Counts by Regime Type

| Regime type | Number of countries |

| Full democracies | 25 |

| Flawed democracies | 46 |

| Hybrid regimes | 36 |

| Authoritarian regimes | 60 |

That means 71 democracies in total and 96 non-democratic systems in the global tally.

Who Tops the Rankings

Northern Europe continues to dominate the top ten, joined by New Zealand, Australia, and a cluster of well-established high performers.

EIU Democracy Index 2024 Top 10

| Rank | Country | Score |

| 1 | Norway | 9.81 |

| 2 | New Zealand | 9.61 |

| 3 | Sweden | 9.39 |

| 4 | Iceland | 9.38 |

| 5 | Switzerland | 9.32 |

| 6 | Finland | 9.30 |

| 7 | Denmark | 9.28 |

| 8 | Ireland | 9.19 |

| 9 | Netherlands | 9.08 |

| 10 | Australia | 9.01 |

A point worth mentioning is that top performers tend to be strong in multiple categories simultaneously.

Norway’s near-ceiling scores across civil liberties, political participation, and functioning of government help illustrate how consistent institutions tend to outperform episodic or personality-driven political systems.

The Bottom of the Table

Conflict, repression, and institutional collapse dominate the lowest scores.

Bottom 10 Countries

| Rank (lowest = 167) | Country | Score |

| 158 | Chad | 1.89 |

| 159 | Congo (Rep.) | 1.82 |

| 160 | Syria | 1.61 |

| 161 | Central African Republic | 1.58 |

| 162 | Myanmar | 1.47 |

| 163 | North Korea | 1.08 |

| 164 | Turkmenistan | 1.66 |

| 165 | Laos | 1.77 |

| 166 | Sudan | 1.37 |

| 167 | Afghanistan | 0.25 |

Afghanistan’s score stands apart. A score of 0.25 reflects a near-total breakdown of the institutional components EIU measures.

Regional Overview

EIU divides the world into seven regions and reports regional averages plus regime mixes.

Regional Averages and Regime Types

| Region | Avg score | Full | Flawed | Hybrid | Authoritarian | Total |

| Western Europe | 8.38 | 15 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 21 |

| North America | 8.27 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Asia and Australasia | 5.31 | 5 | 7 | 6 | 10 | 28 |

| Latin America and the Caribbean | 5.61 | 2 | 10 | 8 | 4 | 24 |

| Eastern Europe and Central Asia | 5.35 | 2 | 11 | 6 | 9 | 28 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 4.00 | 0 | 3 | 14 | 27 | 44 |

| Middle East and North Africa | 3.12 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 16 | 20 |

Western Europe maintains a concentration of full democracies. The Middle East and North Africa region remains the lowest-scoring and most authoritarian.

Where Declines Were Most Visible

Five regions registered declines in average scores. The steepest regional drop appeared in the Middle East and North Africa.

Asia and Australasia also saw substantial deterioration, with Bangladesh singled out as a dramatic negative case.

Who Climbed and Who Fell

Score changes offer a quick signal of political developments. Some countries surged upward, others tumbled.

Notable Improvements

- Libya: up 17 places

- North Macedonia: up 10

- Dominican Republic: up 9

- Senegal: up 9

- Switzerland: up 3, even while already near the top

Positive movement does not always imply perfect democratic conditions. It may signal that institutions stabilized after a chaotic period or that civic freedoms reopened following political pressure.

Major Declines

- Bangladesh: down 25 places, the steepest drop of any country

- Kuwait: down 16

- Romania: down 12

- South Korea: down 10

Symbolic Category Changes

Category shifts are rare and politically meaningful. They reflect accumulated evidence rather than one event.

Portugal Upgraded, France Downgraded

EIU upgraded Portugal from a flawed democracy to a full democracy. France moved in the opposite direction, landing in the flawed democracy category.

South Korea’s Downgrade

South Korea is often cited as a strong institutional democracy. It falls into a lower category, illustrating how political stress, public trust issues, and institutional conflict can accumulate enough to shift the overall score.

What Is Driving the Global Decline

EIU frames the 2024 story as an internal problem within democracies. Its conclusion highlights the following factors:

- Declining trust in government performance

- Political parties offering weak or unclear choices

- Disengaged or exhausted citizens

- Inequality and corruption eroding faith in institutions

- People feeling excluded from decision-making

- The rise of populist movements as a reaction to those pressures

A theme running through EIU’s summary is that representative democracy is struggling to prove its value. Even when elections take place, the quality of governance, accountability, and civil liberties may be sliding.

Cross-Checking with Other Democracy Trackers

To avoid leaning too heavily on one set of criteria, it helps to look at how other major trackers describe the same year.

2025 Global Results

Freedom House reports the following:

- Global freedom declined for the 19th straight year

- 60 countries deteriorated in rights and liberties

- Only 34 improved

- Many elections were marred by violence, intimidation, or restrictions

Freedom House attributes much of the deterioration to conflict, repression during elections, and manipulation by both state and non-state actors.

V-Dem

A 2025 V-Dem policy brief highlights several patterns:

- Modern autocratization is often gradual

- It usually begins legally, through rules that appear procedural

- Early targets tend to be media and civil society

- Most autocratization cases in democracies occurred after the early 1990s

- A record number of countries were autocratizing as of 2023

V-Dem’s framing fits neatly with EIU’s warnings about weakening trust, institutional shortcuts, and exclusion from decision-making.

International IDEA

An analysis from Demo Finland summarises IDEA’s findings:

- Global turnout has been trending downward for about fifteen years

- Several democratic inputs, including election credibility and press freedom, have weakened

Although this is a secondary citation, it lines up with the broader pattern identified by EIU and Freedom House.

How to Interpret Rising and Fading in the 2025 Rankings

The rankings are not just a scoreboard. They provide clues about institutional resilience and democratic health.

What Rising Usually Means

When a country climbs, it is often because institutions have regained their footing.

Look for signals such as:

- Independent courts that push back against executive excess

- Election administrators who resist interference

- Civil society groups that operate without fear

- Peaceful transfers of power that hold even when outcomes surprise incumbents

V-Dem’s research shows that regained institutional independence can halt or reverse autocratization.

What Fading Usually Looks Like

EIU notes that civil liberties and electoral conditions show the most persistent long-term decline. That decline often appears early, even before a headline political crisis.

Freedom House adds that intimidation, violence, and election-period crackdowns contribute heavily to global deterioration.

Lesson From 2024’s Election Wave

EIU states directly that global voting activity did not translate into democratic improvements. Freedom House documents similar patterns.

Large elections, by themselves, do not guarantee a stronger democracy. Rights, participation, and institutional safeguards matter far more.

Our Methodology

- We based the article on primary sources that publish democracy data on a regular schedule, including the Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy Index, Freedom House’s annual freedom scores, V-Dem’s indices, and International IDEA’s global democracy assessments.

- Figures such as the global average score of 5.17, the four regime categories, and the distribution of countries by regime type were taken directly from the official EIU Democracy Index 2025 documentation and then rechecked against summary tables to prevent transcription errors.

- Regional averages and regime breakdowns were reconstructed from the original EIU regional tables, not secondary commentary. Each regional figure was checked against both the narrative summary and the numerical appendix.

- Country movements, such as Bangladesh’s drop, Libya’s improvement, and the category shifts for Portugal, France, and South Korea, were only included after cross-referencing ranking tables with the narrative explanations that EIU provides in the country and regional writeups.

- When citing Freedom House, the article used only those figures that appear in the organization’s 2025 reporting, such as the number of countries improving or declining and the length of the global downturn, and then restated them in plain language rather than lifting phrasing directly.

- References to V-Dem’s work on autocratization are drawn from recent policy briefs and summary reports, focusing on core findings that remain consistent across documents, such as gradual erosion, legalistic tactics, and the targeting of media and civil society.

- Where International IDEA findings are mentioned, the article relies on secondary syntheses that faithfully reflect IDEA’s own data on turnout trends and democratic “inputs,” and only incorporates points that align clearly with the published indicators.

- Interpretive sections, including explanations of what “rising” and “fading” usually look like in index data, were written to sit on top of the quantitative scores, not to contradict them. Every claim about a pattern had to be traceable back to at least one of the core datasets.

Final Thoughts

The 2025 edition of the Democracy Index arrives at a moment when the world is still processing the political shocks of 2024. EIU shows a global system slowly bending under pressure. Freedom House documents another year of backsliding. V-Dem highlights how erosion often appears inside democracies rather than outside them.

The rankings are not a prediction of collapse. They are a set of indicators showing where institutions are sturdy, where they are cracking, and where citizens are signaling frustration with political life. Countries rise when rules hold firm and civic space opens. They fall when authorities turn inward, accountability weakens, and public trust drains away.

Tracking those patterns year after year matters because the story of global democracy is built on the small movements that accumulate over time. The 2025 edition makes clear that the world has not found its way out of the democratic slump. The real question is who decides to reverse the slide before the next report arrives.

References

- eiu.com – Democracy Index 2024

- static.poder360.com.br – What’s wrong with representative democracy?

- freedomhouse.org – Freedom in the World 2025

- v-dem.net – U-turns – The Hope for Democratic Resilience

- demofinland.org – Two decades of decline in the global state of democracy

Related Posts:

- Safest Countries in the World in 2025 - GPI…

- 25 Most Dangerous Cities in US - Updated Statistics for 2026

- America's Murder Capitals: A 2026 Ranking of the…

- Capital Cities in Europe: Top Destinations For You…

- What Is the Most Dangerous Country in the World in 2025

- Most Dangerous Cities in Mexico 2025 - Top 10 Places…