Loneliness once lived in the background. A quiet feeling that surfaced during slow evenings or transitional moments, then faded as routines kicked back in.

In 2025, loneliness looks different. It shows up in surveys, health advisories, workplace data, and generational research. It appears not as a rare emotional state, but as a recurring condition tied to how Americans live, work, and move through daily life.

Recent findings linked to the American Psychological Association Stress in America survey work report that 54% of U.S. adults feel isolated from others often or some of the time. Half of adults report feeling left out. Half say they lack companionship.

Those numbers describe something structural. Emotional disconnection has become common enough to register at the population scale.

That raises a practical question worth answering carefully: which generation feels loneliness most, and why does it concentrate where it does?

Table of Contents

ToggleKey Points

- Gen Z feels loneliness the most, with 67% classified as lonely, followed closely by Millennials at 65%.

- Younger adults report loneliness far more often than older age groups, across multiple major surveys.

- Loneliness is widespread, with 54% of U.S. adults feeling isolated often or some of the time.

- Impact differs by age; loneliness is more frequent among younger adults ,but often more damaging when it becomes chronic later in life.

America’s Loneliness vs. Social Isolation – Two Different Experiences

Loneliness and social isolation often get lumped together, yet they describe different things.

Loneliness refers to a felt gap. It is the distance between the relationships someone wants and the relationships they actually experience.

Social isolation is more concrete. It describes fewer interactions, fewer social roles, fewer close connections, and less frequent contact.

The World Health Organization uses the same distinction in its definitions. Loneliness is subjective and painful. Social isolation is objective and measurable.

A person can attend meetings all day, message family, scroll social media, and still feel lonely. Another person can live alone and feel well supported. Much of the modern loneliness problem sits in that first category: contact exists, yet emotional support feels thin.

The Headline Number That Changed the Conversation

The 54% isolation figure comes from reporting tied to the APA’s 2025 Stress in America findings we mentioned earlier.

It connects emotional disconnection with broader strain, especially stress related to social division and daily pressures.

Key numbers from the same set of findings include:

- 54% feel isolated from others often or some of the time

- 50% feel left out

- 50% lack companionship

Those percentages matter because they frame loneliness as routine rather than exceptional. Many people who meet basic life demands still feel socially unmet.

That also explains why loneliness often travels alongside fatigue, anxiety, headaches, and sleep disruption. The body reads social safety as a real input, not an optional emotional bonus.

Which Generation Feels Loneliness Most in the U.S.?

The data makes one pattern hard to ignore: feelings of loneliness are not evenly spread across age groups, and some generations carry a much heavier share than others.

Generational Data Points to Gen Z

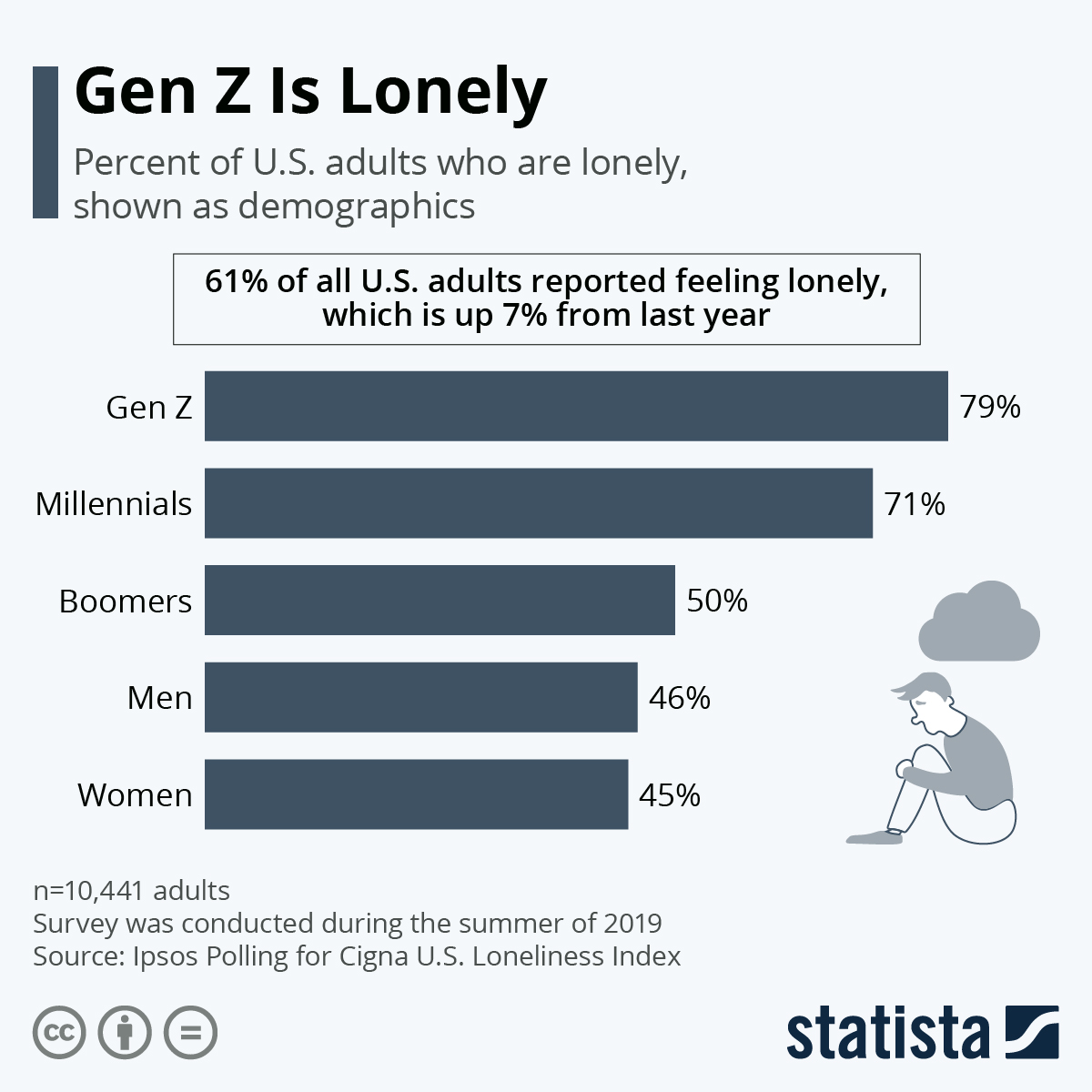

One of the most detailed generational breakdowns comes from The Cigna Group and its 2025 Loneliness in America reporting, drawing on the Vitality in America 2024 study.

Cigna’s classification of loneliness by generation looks like this:

| Generation | % Classified as Lonely |

| Gen Z (born 1997–2006) | 67% |

| Millennials (born 1981–1996) | 65% |

| Gen X (born 1965–1980) | 60% |

| Baby Boomers (born 1946–1964) | 44% |

The answer is clear. Gen Z reports the highest loneliness levels, with Millennials close behind.

Cigna also adds an important nuance. Younger generations show higher rates of loneliness classification, yet older adults often experience sharper drops in mental health and vitality when loneliness becomes chronic. Frequency and impact do not always line up neatly.

Looking at Age Groups Instead of Labels

Generational names help storytelling, but many large surveys rely on age brackets.

A Pew Research Center survey conducted Sept. 3–15, 2024, found:

- 16% of all adults feel lonely or isolated all or most of the time

- 24% ages 18–29

- 20% ages 30–49

- 11% ages 50–64

- 6% ages 65+

Here is the same data in table form:

| Age Group | % Lonely or Isolated All or Most of the Time |

| All adults | 16% |

| 18–29 | 24% |

| 30–49 | 20% |

| 50–64 | 11% |

| 65+ | 6% |

Different method, same pattern. Younger adults report loneliness far more often.

Why Gen Z Shows Up as the Loneliest Generation

Gen Z consistently ranks highest in loneliness surveys, a pattern tied to fragmented social routines, constant life transitions, and relationships that exist in volume but often lack depth.

Social Life Feels Busy Yet Thin

Gen Z often maintains more messages, more group chats, and more online presence than any generation before. Emotional weight does not automatically follow.

The U.S. Surgeon General’s advisory on social connection points to a long-term shift in how relationships function. Technology increased contact, yet the structure and quality of the connection weakened.

Common Gen Z social patterns include:

- Frequent light-touch interactions

- Fewer high-trust relationships

- Fast turnover from school to college to jobs

- Relocation that resets social networks

- Fewer stable third places like community hangouts

Relationships exist, yet they often fail to carry people during stress.

Early Adulthood Runs on Constant Transition

Young adulthood stacks transitions tightly:

- Leaving home

- Moving cities

- Switching jobs

- Dating through apps

- Living with rotating roommates

Loneliness spikes when routines break faster than the community can form. Stability matters more than volume.

Repeated Signals Across Data Sources

Younger adults appear consistently in high-loneliness findings beyond Cigna.

The Surgeon General’s advisory notes that many surveys show about half of U.S. adults experience loneliness, with especially high rates among young adults.

Gallup data aggregated from 2023–2024 shows 25% of U.S. men ages 15–34 felt lonely a lot of the previous day .

That framing matters. It captures loneliness as a lived daily experience, not a vague life summary.

Why Millennials Sit Close Behind

Millennials rank just behind Gen Z at 65% classified as lonely in Cigna’s reporting.

The profile often looks different. Millennials tend to carry more responsibility with less discretionary time:

- Long work hours

- High housing costs

- Parenting young children

- Caregiving for family

- Relocation that breaks local ties

Cigna highlights one especially relevant group: parents of young children and unpaid caregivers, where about two-thirds are classified as lonely.

That version of loneliness can feel confusing. Life stays busy. People stay needed. Emotional support still feels absent.

Gen X

Gen X comes in at 60% classified as lonely.

Loneliness here tends to run quieter. Less public. Less discussed. It often ties to:

- Work stress with limited flexibility

- Career plateaus or job insecurity

- Caring for both children and aging parents

- Shrinking friendship circles due to time limits

Cigna reports that lonely Gen X adults rate their mental health significantly lower and report higher depression or anxiety compared with non-lonely peers.

Social life in midlife runs on maintenance. When friendships fade, replacing them becomes genuinely hard.

Baby Boomers

Boomers show lower loneliness classification at 44% , and Pew data shows adults 65+ are least likely to report frequent loneliness.

Yet when loneliness appears later in life, it often runs deeper. Triggers tend to be structural:

- Bereavement

- Retirement and loss of daily roles

- Reduced mobility

- Chronic illness

- Moving away from long-term communities

Cigna notes that lonely older adults report much worse mental health than peers who remain socially connected. Frequency is lower. Impact is heavier.

Loneliness Does Not Spread Evenly Inside a Generation

Age alone never tells the full story.

Income and Relationship Status Matter

Pew reports that unpartnered adults are more likely to feel lonely or isolated. Loneliness also varies by education and income.

The Harvard Graduate School of Education has highlighted links between loneliness and socioeconomic stress, with higher loneliness reported among lower-income groups.

Gender Differences Depend on Context

Men and women report similar overall loneliness frequency, yet differ in how they seek support.

Gallup adds an important note. Young men in the U.S. stand out compared with peers in other OECD countries, showing unusually high loneliness patterns.

Broad gender headlines miss the detail. Specific life stages and social roles shape risk far more than gender alone.

Health Consequences Recognized by Public Health Authorities

Loneliness moved into the spotlight because the health effects became difficult to ignore.

The U.S. Surgeon General’s advisory frames social connection as a fundamental human need and reports that millions of Americans lack adequate social connection in one or more ways.

It describes loneliness as widespread, reaching prevalence levels comparable to many major health concerns.

The World Health Organization goes further. Its Commission on Social Connection links loneliness to an estimated 100 deaths every hour, totaling more than 871,000 deaths annually worldwide.

Health outcomes associated with chronic loneliness include:

- Higher depression and anxiety risk

- Cardiovascular strain

- Sleep disruption

- Cognitive decline risk in older adults

- Increased all-cause mortality

Loneliness now sits firmly in the public health category.

Work as a Major Loneliness Accelerator

Work has changed faster than social structures adapted.

Common shifts include:

- Fewer stable teams

- Remote and hybrid arrangements

- Less spontaneous interaction

- Weaker workplace community

Cigna reports that lonely employees are more likely to disengage, miss work, or look for a new role. Costs ripple outward from individuals to organizations.

Workplace loneliness also reinforces itself. Disconnection leads to withdrawal, which limits bonding, which deepens disconnection. Breaking that loop requires intentional design.

Why “Everyone Is Lonely” Misses the Point

High loneliness numbers do not mean everyone feels the same thing.

Surveys measure different layers:

- Frequency of loneliness

- Intensity of emotional pain

- Perceived social support

APA reporting captures how often isolation feelings appear. Pew focuses on the highest frequency category. Cigna classifies loneliness across multiple vitality and belonging indicators.

Those approaches measure different parts of the same landscape.

What Actually Helps

No single fix exists. Effective responses rebuild routine social structure rather than chasing quick emotional boosts.

Increase Repeated, Low-Pressure In-Person Contact

Social life improves when treated as a rhythm rather than events.

Practical examples:

- The same gym class 2–3 times per week

- Regular volunteer shifts

- A standing weekly coffee

- Clubs with expected attendance

Cigna finds that people engaged in cultural events, volunteering, or religious services show stronger well-being resilience.

Reduce Life Admin That Crowds Out Connection

People rarely fail socially due to indifference. Time pressure does more damage.

Millennials and Gen X often need:

- Childcare swaps

- Predictable work hours

- Shorter commutes

- Fewer financial side hustles

Freeing even a few hours per week allows relationships to regrow.

Build Support That Is Specific

View this post on Instagram

A post shared by Dr Preeya Alexander MBBS FRACGP CEDC-GP (@doctor.preeya.alexander)

Many lonely adults have someone to text. Fewer have someone who would:

- Drive them to an appointment

- Watch children briefly

- Sit with them after bad news

The Surgeon General’s advisory stresses that connection quality and function matter more than contact volume.

Treat Loneliness as a Health Input

The biggest shift of the past decade is framing loneliness as a health factor rather than a personal flaw.

WHO messaging makes the case directly. Social connection influences health, education, productivity, and longevity at scale.

That framing replaces shame with action.

So, Which Generation Feels It Most?

Based on high-authority reporting, Gen Z reports the highest loneliness classification at 67% , followed closely by Millennials at 65% .

Pew’s age-based data supports the same pattern. Younger adults report loneliness far more often.

The 54% isolation figure tied to APA Stress in America reporting shows how widespread emotional disconnection has become across adulthood.

Loneliness touches every generation. Younger adults sit at the leading edge. Long-term damage often lands hardest when isolation becomes chronic and difficult to reverse.

The data points to a clear conclusion. Loneliness is no longer a private feeling. It is a shared social condition shaped by how life is structured in modern America.